We hardly ever do this at Aaron | Sanders, that is, talk about cases that have just been filed and for which there is no actual judicial opinion yet. We refrain from talking about newly-filed cases for two main reasons: 1) There are too darn many of them and 2) It forces us to end the post by saying something totally lame like “Stay tuned….” But I couldn’t resist this time. For starters, I adore Sherlock Holmes (in no small part because of his recent resurrection in the body of Benedict Cumberbatch, but also because he said it better in A Study in Scarlet than any lawyer ever did: “I listen to their stories, they listen to my comments, and then I pocket my fee.“). But also the copyright issues in the case raise some pretty good questions which will almost certainly come up again, in circumstances that are less clear even than here.

The case of which I speak is currently styled Klinger v. Conan Doyle Estate, Ltd., and is pending in a District Court in Illinois. Leslie Klinger is a well-known expert in “those twin icons of the Victorian era, Dracula and Sherlock Holmes.” (Check out his website, but please don’t stare too long at the cover of “Sandman”…..). His authority on the enigmatic sleuth has led him to pen a collection of new Holmes tales currently titled “In the Company of Sherlock.” The Doyle estate insists that Mr. Klinger needs a license in order to publish his book, citing the following facts:

Doyle published his first Holmes novel, “A Study in Scarlet,” in 1887, and continued to write about the detective from Baker Street for the next four decades. The last ten Holmes novels were published after 1923. 1923 is a magic date in U.S. copyright law, because everything published before that date is in the public domain.*

*Except Happy Birthday.

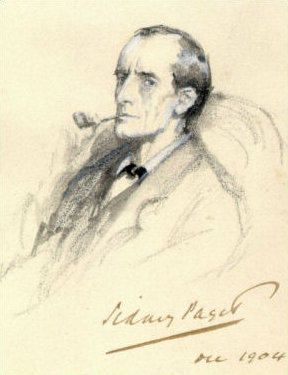

Holmes, 1904 (Sharet)

The question in the case, then, is fairly obvious. Are the elements of Holmes that appear in Klinger’s new collection in the public domain or not? The Doyle estate is of course arguing (and I must say, beautifully) that Holmes was created in a “non-linear way,” built with new backgrounds and outlooks woven throughout all the stories of Doyle, including the ten that are still copyrighted, in a way that is impossible to separate on a timeline. “A complex literary personality,” the lawyers state, “can no more be unraveled without disintegration than a human personality.” (One can argue whether certain human personalities could have certain aspects removed, with the result being a net positive). The Doyle estate would very much like to frame the creation of Homes and Watson as an arc, in which elements built upon each other to create personae which we now know and love can not possibly be broken into their chronological parts. In this case, the estate may not find the law on their side. Joel Siegl’s heirs found their interest in the Superman character reduced to “the image of a person with extraordinary strength who wears a black and white leotard and cape,” in the Central District of California in 2008, when it turned out that this was the only image that was published on a date late enough for the Siegls to have termination rights in it. Not a public domain case, but a good example that courts are happy to disassemble iconic characters into their component fictional parts. Here, we likely have clear textual evidence of which parts of Holmes and Watson existed in books published before ’23 and which didn’t. And although we agree that “It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data,” so long as Klinger stays on the left side of the timeline, we are guessing the court will side with him.

But of course, stay tuned….