Did the Ninth Circuit Contradict Itself?

A few days ago, we got two opinions handed down by the same court, written by the same judge, on essentially the same subject, involving the same defendant that reach seemingly contradictory results. On July 31, the Ninth Circuit handed down two decisions about the use of likenesses in video games: Brown v. Electronic Arts, which went defendant’s way, and Keller v. Electronic Arts, which went the plaintiffs’ way.

In both cases, football players sued video-game maker EA for using their likenesses in EA’s football video games. Jim Brown, perhaps the greatest football player ever*, objected to the use of his likeness in EA’s Madden NFL**. In Keller, several former college football players, none of whom will ever be considered one of the greatest of all time, objected to the use of their likenesses in EA’s NCAA Football.

* Before even my time, though.

** EA licenses with the NFL and NFL Players Association for the rights to use players’ likenesses, but Brown has been far too long retired to be covered by those licenses.

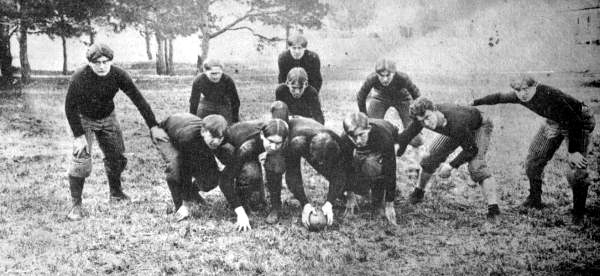

These guys might be suing next, when EA comes out with Old-Timey College Football.

The way these two decisions have been reported and discussed is that Brown lost because he had brought trademark claims (i.e., use of his likeness to create a sense of endorsement), while the Keller plaintiffs won because they had brought right-of-publicity claims. This made people wonder if Brown’s attorneys were morons: how could they miss the right-of-publicity claims? The truth is, they didn’t. It would be more accurate to say that the Ninth Circuit considered only Brown’s trademark claims, because Brown did, in fact, have right-of-publicity claims, too; they just weren’t before the Ninth Circuit. It is accurate to say that Brown’s trademark claims failed and the Keller plaintiffs’ right-of-publicity claims succeeded because of the different ways (according to the Ninth Circuit) the free-speech right of the First Amendment interact with those claims.

Brown’s Publicity Claims Weren’t Well Publicized

So, why didn’t the Ninth Circuit consider Brown’s publicity claims? Ironically, it was because he brought trademark claims. Trademark claims are governed by both federal law (“Lanham Act”) and state law, whereas publicity claims are governed exclusively by state law. Brown was in federal court because he had a federal claim. OK, what were the Keller plaintiffs doing in federal court with their state-law claims? Unlike Brown, who is apparently a resident of EA’s home state of California, the Keller plaintiffs were from different states, which forms another basis for federal jurisdiction. But the upshot for Brown was that, if his federal trademark claim was killed, his state-law claims, including his publicity claims, would go away. Without any federal claims, the court would just divest itself of jurisdiction.

This is important: Brown’s state-law claims didn’t die. They remain alive. They just have to be brought in state court. I fully expect Brown to re-file his publicity claims in state court if he can’t somehow reverse the Ninth Circuit’s decision.

Then, why didn’t the Keller plaintiffs bring trademark claims? Because, while trademark claim is quite plausible for Brown, it isn’t very plausible for former college players who never went onto any fame. Brown, by contrast, is not only the greatest football player ever, but he was also an actor and a sometime activist. If Brown endorsed, say, a brand of orange juice—or, I don’t know, a football video game—that’d mean something. If any of the Keller plaintiffs did….

Jim Brown Wasn’t Known for Dancing

This brings us to Brown’s trademark claim. Video games are expressive, so the free-speech right of the First Amendment has something so say about whether Brown can enforce his trademark claim. The case law is not completely stable on this issue, but courts are definitely coalescing around a well-understood and well-established test for whether the right of free speech can block a trademark claim: the “Rogers test, named after none other than Ginger Rogers, who objected to the use of her name in the Fellini movie Ginger and Fred. I’ve discussed this test several times before: here, here and here. The nub of the rule is that trademark law should apply to artistic works only if ”the public interest in avoiding consumer confusion outweighs the public interest in free expression.“ In balancing those two interests, the Rogers test came down pretty firmly on the side of free speech: free speech will block a trademark claim, unless either (1) the use of the trademark has ”no artistic relevance to the underlying work whatsoever“; or (2) it ”explicitly misleads” the consumer about, for example, endorsement.

This is a very difficult standard to overcome, and Brown wasn’t able to overcome it. Brown’s likeness and statistics were used to, in essence, simulate the thrill of playing Brown. This use clearly has artistic relevance to Madden NFL. EA was also careful not to create any direct impression that Brown endorsed the game.*

* Remember, the First Amendment is effectively raising the bar on Brown here. He would otherwise have a pretty good case that he’s being made to endorse the game when he didn’t want to.

Keller Has Hart, So He Doesn’t Need to Dance

But Brown has to be feeling bullish about his publicity claims, when he gets around to re-filing in state court, because of what happened in Keller. In that case, EA was making an early challenge to the plaintiffs’ ability to back up their case with evidence.* The plaintiffs got rather more than that from the court: they got a ruling that EA’s free-speech defense failed, leaving EA quite vulnerable when the case is sent back down to the trial court.

* Via what is known as an “Anti-SLAPP” motion. SLAPP stand for “strategic lawsuit against public participation,” and SLAPP laws are meant to discourage lawsuits that affect free speech. California’s is among the toughest. One feature is that the defendant can force the plaintiff to make an early showing that they have enough evidence to make a case—not necessarily a winning case, but a case. It’s a bit like an accelerated motion for summary judgment. Since EA had a free-speech interest in NCAA Football, it qualified to bring an “anti-SLAPP” motion.

The Keller plaintiffs won for pretty much the same reason Hart won in a very similar situation before the Third Circuit. The Ninth Circuit agreed with the Third Circuit that the Rogers test was inappropriate for publicity claims. I explain the Third Circuit’s reasoning here.

Instead, the Ninth Circuit applied at test sort of borrowed from copyright law: the transformative test. If the use of the likeness is “so transformed that it has become primarily the defendant’s own expression rather than the … likeness,” free speech will block the publicity claim. As I put it in my blog post, if the celebrities whose likenesses you’re using is essentially “star as themselves,” then you’re not being transformative enough. And just as No Doubt starred as themselves in Band Hero, and Hart starred as himself in NCAA Football, so the Keller plaintiffs star as themselves in NCAA Football.

The Social Network Problem

It has been objected that, under this rule, it should be impossible to make biographic works of living (or, in some states, deceased) persons, or even documentaries. The movie The Social Network should have been impossible because “it literally recreates Zuckerberg in the very setting in which he achieved renown.”. Put another way: why should the First Amendment be weaker against publicity rights, which are amorphous, newfangled, and really only of much value to celebrities, than against trademarks, which are central to commerce and quite ancient?

That’s not the case, fortunately, though the Ninth Circuit’s reasoning would certainly lead us in that direction. For example, in Dora v. Frontline, the court rejected the publicity claims of a surfer who appeared in a documentary about surfing.* The court invoked a different free-speech-like defense: “matters of public interest.” The court reasoned that the documentary, and the use of the surfer’s likeness, was a “fair comment on real life events which have caught the popular imagination.” Similarly, when Joe Montana sued a newspaper for selling posters of previously published pages of the newspaper about the 49ers’ Super Bowl Victories, and which featured pictures of Montana (naturally), the court threw that claim out, as well. “Posters portraying the 49ers’ victories are … a form of public interest presentation to which protection must be extended.”

* Ironically, the EFF staffer whose criticism I’ve been paraphrasing is himself a surfer, but apparently hadn’t heard of this case.

You might think that this “public interest” defense would protect something like The Social Network. Surely, the rise of Facebook is something that has “caught the popular imagination,” right? Well, not if you draw the same lessons from these “public interest” decisions the Ninth Circuit drew. The Ninth Circuit appeared to limit the defense to “publishing or reporting factual data” and that EA’s defense fails because “it is a game, not reference source.”

Well, The Social Network is a movie, not a reference source.

Under the Ninth Circuit’s view, either you should transform a lot, or not transform at all. A movie like The Social Network falls right in between: it’s not a documentary, but a work of fiction in which an actor plays Zuckerberg playing himself.

Why Doesn’t Public Interest = Public Interest?

The Ninth Circuit might have drawn a different lesson: that public interest means public interest. I know, crazy. And amorphous. And potentially overbroad. But, then, publicity rights are amorphous and potentially overbroad. The result would have been the same for the Keller plaintiffs and for Hart, but for Jim Brown…?

It’s no secret that I’m sympathetic with Keller and Hart because the NCAA was able to license their rights for itself.* But surely there’s a line to be drawn between Keller, Hart and No Doubt on the one hand, and Dora (the surfer), Joe Montana, baseball players whose statistics are used for “fantasy baseball,” Mark Zuckerberg in The Social Network, and Tony Blair and the Queen of Great Britain in The Queen, on the other hand. There will be hard cases in the middle, like Jim Brown in Madden NFL, where his fame could hurt his case.

* I’m also a little sympathetic with EA, since it faces the prospect of paying twice for the same rights: once to the NCAA, and again to the players. So the villain here is the NCAA, which gets to keep the money.

Perhaps, instead of separate “transformative” and “public interest” tests, we should combine them into a test that weighs both the centrality of the likeness to the artistic endeavor and the public interest in the subject matter of the endeavor against one’s interest in one’s own image. Such a test would explicitly capture in-between cases like The Social Network and The Queen. We could even call it the publicity version of fair use.

What Is So Important About Publicity Rights?

Of course, such a balancing test would be a lot easier if we knew more about the other side of the equation: what is it that publicity rights protect? With trademark rights, the answer is easy: the avoidance of consumer confusion. With publicity rights, what exactly are we worried about, from a Constitutional point of view? What, exactly, is promoted by strong enforcement?

To turn the question around a bit: what is it about our publicity rights that should trump free speech? Before you answer that, remember that free speech (looked at from this end) is curtailed in many legal situations: copyright (where it’s baked into fair use), trademark (ditto), defamation (particularly for non-public figures), solicitation to commit a crime, many other crimes that involve expression, so forth. Thus, in the case of defamation, for example, one’s reputation is significantly important that we’re willing to curtail free speech at least a little bit.

Is it just the weird privacy-oriented sense that people are looking at your image? The publicity right is, after all, said to be a species of one’s right to privacy. But, no. It’s also described as a property right, and that it goes to things like reputation or prestige, which sounds rather like a kind of trademark right. Neither sense would quite cover the situation of the model, whose livelihood depends on his or her appearance and ability to restrict access to his or her likeness.*

* Adding to the confusion are statutory versions of the publicity right, most notably in California (movie stars), New York (stage stars), Tennessee (Elvis) and Indiana (????), which might define the right rather differently.

No one really knows, and that’s part of the problem. It has always looked like two different rights: a privacy right (the right not to have your image publicized), and a purely economic right (the right to control access to you appearance). Ordinary folks benefit from the first one, models from the second, and celebrities from a little of both.

Thanks for reading!