You Can Strike a Pose, but Can a Pose Be Striking?

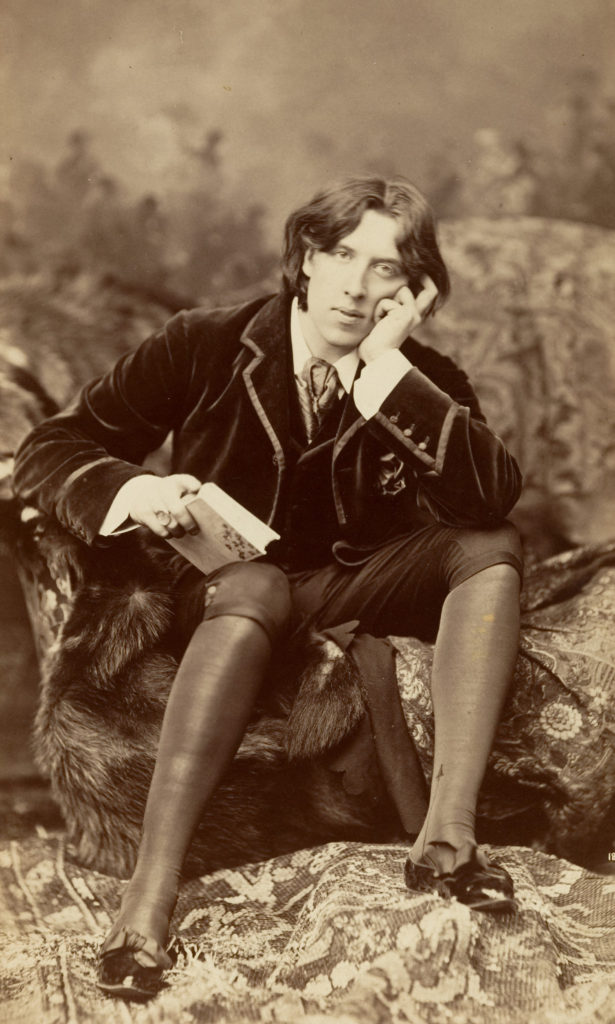

Ages ago, I started off my copyright courses with a couple of old but good photography cases, as a way of stretching the students’ minds about what constitutes “copying” and what constitutes “creativity.” The first photograph was this famous portrait of Oscar Wilde by Napoleon Sarony1The “Napoleon” of Broadway photography. Sorry., who was known for its fastidiousness in posing subjects:

Napoleon Sarony’s portrait of Oscar Wilde (who hopes you continue to talk about him, as he stares into your soul)

When the photographer sued to stop knockoffs of this photograph, he had first to prove that photographs were even protectable. Photography was still a relatively new technology, and many artists sniffed at it. How could it be creative, when all it does is capture exactly what it sees? It is merely mechanical, not creative, they said. The Supreme Court disagreed, holding that photography could indeed be protected by copyright. Yes, Oscar looks like Oscar, and the photographer can’t do much about that, but there is a lot that the photographer can do something about. Not only could he pick out the right clothes, the right chair, the right drapery, etc., but he could also arrange the lighting (and the camera angle and some other things the Court didn’t think of). Oh, and he could control Oscar’s expression. Anyway, the Supreme Court held that there was a valid copyright in the photograph, a milestone in the history of photography.2The copyright act in force at the time specified photographs as protectable, but many felt that the inclusion was unconstitutional, on grounds that photographers aren’t “authors.”

When Maybe You Shouldn’t Steal From Yourself

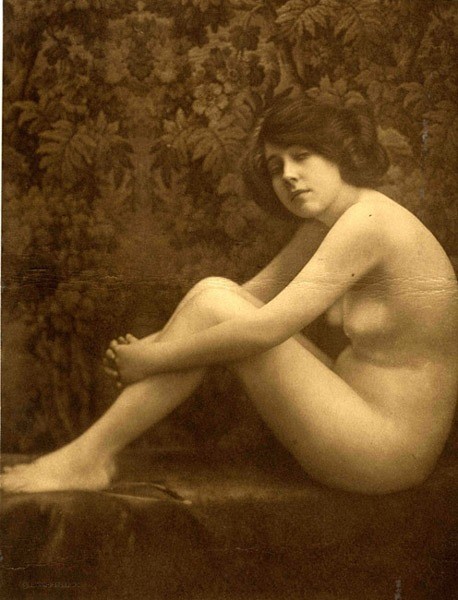

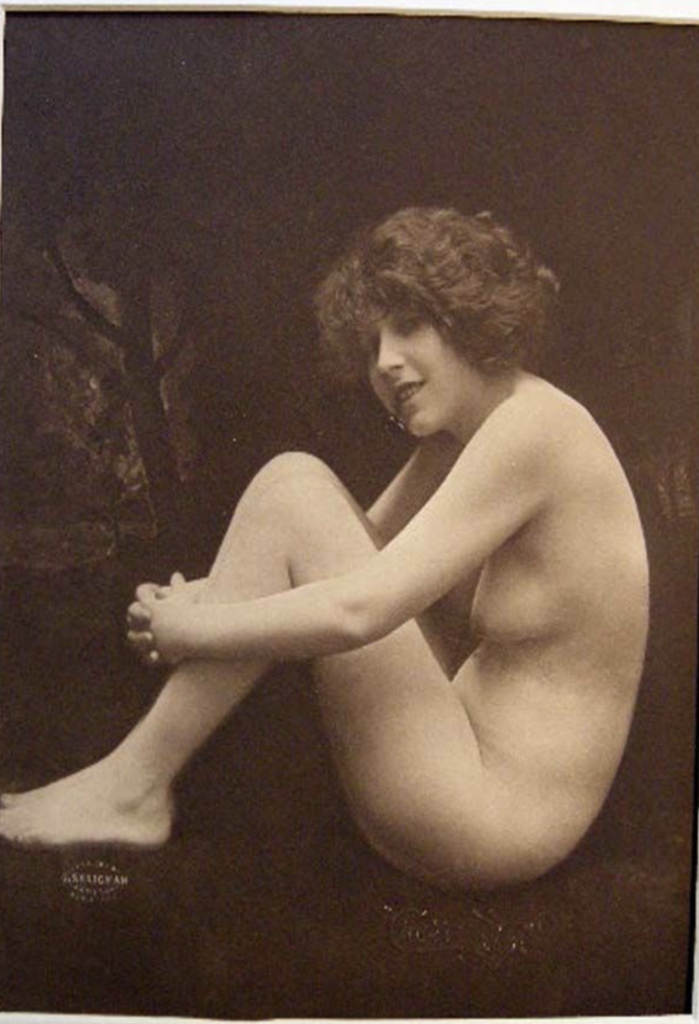

Not long after came a case involving these two photographs, “Grace of Youth” and “Cherry Ripe.”

As you can tell, these are two different photographs taken at different times. They are of the same model, and they were taken by the same photographer.3Who was the defendant in the case. No, he didn’t sue himself. He sold the copyright in “Grace of Youth” then tried to re-create the pose and got sued by the new owner of the copyright in “Grace of Youth.” Yet, the court held that “Cherry Ripe” infringed the copyright in “Grace of Youth.” Clearly, it all came down to the pose, angle and maybe lighting: a nude woman (actually, she’s the same model), photographed from the side, with her knees pulled up half-way, her arms clasped around her shins, and her face turned three-quarters. There’s some similarity in the way the shading falls, but the shading in “Cherry Ripe” is much starker. Even so, the poses aren’t identical, though they’re pretty close. The model in the right-hand photograph has her knees pulled up higher, and she has the trace of a smile on her face.4Or maybe she can’t help it. She’s got a cherry stem between her teeth.

The “Grace of Youth” decision was, and remains, controversial, whereas the Oscar Wilde decision is regarded as one of the truly important copyright decisions. I’m not sure how many courts would today agree with “Grace of Youth,” and it might really be an anomaly. Nevertheless, there’s an important takeaway from the “Grace of Youth” case: you can infringe copyright not only by copying in the ordinary sense, but also by re-creating.

If nothing else, “Grace of Youth” case at least suggests the possibility copyright will protect a pose. Still, what additional changes would the Second Circuit allow to “Cherry Ripe” and still call it infringing? What if the model turned her head? What if she didn’t clasp her hands? What if her hands were palm-down on the ground? What if her knees were pulled up even higher? What if she weren’t nude? What if… she weren’t the same model? What if… it weren’t the same photographer? The opinion lacks the detailed reasoning (typical of its time) to allow us to guess.

Posing Things and Ideas

Now imagine that the photographer didn’t pose people but things. Let’s say she took various found objects and posed them together then took a photograph of that. We’d all agree that, if someone re-created the positioning of the objects and photographed them, there’d at least be a strong likelihood of infringement, even if the photography elements were pretty different (e.g., different angle, different lighting, etc.).5Let us put aside the equally fascinating question of whether the first photographer has a separate copyright in a sculptural work, and that the second one infringed that copyright even before he took the photograph.

Why are we more hesitant to protect the posing of people than things? In the hypothetical above, we gave the first photographer almost limitless possibilities about what to select and how to arrange it all. By contrast, there are only so many ways to pose a human body. There are fewer ways to pose a human body comfortably. And there are, in addition, some poses that are part of any portrait-photographer’s repertoire. Among copyright lawyers, this last set falls firmly under the rubric of “scènes-à-faire,”6A term borrowed from stagecraft and playwriting, which referred to stage conventions so powerful that playwrights couldn’t ignore them. The term is obviously expanded in a couple dimensions for use in copyright law. though you might helpfully think of it as part of artists’ common toolbox: stock characters, stock techniques, stock modules, and, here, stock poses.7Don’t be fooled by my repetition of “stock.” Stock photography isn’t a scène à faire, for example.

Let’s go back to the photograph of Oscar Wilde, and let’s pretend that it’s still under copyright.8It isn’t. If you wanted to take a photograph of someone sitting down, could you? Sure! Sitting down is a normal position for a human being, so it’s a scène à faire. What about book and resting the cheek on the hand? Fine and fine.

Enough of this. At some point, you’ll cross a line and will be infringing. Where’s that line? That’s a matter of debate. Also, it’s not so much a line as a fuzzy zone where a jury might or might not find infringement. I happen to think you would have to get quite close to the original, especially if you ditched the period clothes. But I think it’s also possible. The pose is the result of dozens of creative decisions.

But here’s the thing. We’re not really protecting a pose, but a photographic representation of a pose. A pose, in and of itself, isn’t fixed in a tangible medium of expression9Your skin might be a tangible medium of expression, i.e., for tattoos, but your body overall isn’t.. So the other aspect that’s crucial is the camera angle. If you, through necromancy (perhaps), exactly duplicated the Oscar Wilde pose, but took the photograph from the side, or from above, or from sharply below, I don’t think you’d be infringing. It’s not the pose, but the way the pose is captured on the print.

Be Like Mike (But Not That Much)

This brings us up to a couple of famous, even iconic, photographs. Michael Jordan doing a grand jetè with basketball extended toward a basket. A grand jetè is not a normal human pose, unless you’re a ballet dancer. It’s a high leap with the legs extended, one forward, one back. Basketball players don’t normally perform a grande jetè even incidentally when leaping toward the basket for a slam. But there is a thought that some basketball moves close to the basket are like ballet. The creative thought was to combine a highly recognizable ballet move with a highly recognizable basketball play.

That idea belonged to Jacobus Rentmeester, who had a then-collegiate Michael Jordan perform the grand jetè. Because of the implied motion, the photograph appears spontaneous, but really, Rentmeester was meticulous in how he staged it, instructed Jordan and took the photograph. It would be published in Life magazine, where it would be justly celebrated.

After Jordan left college, he entered into a sponsorship deal with Nike, and Nike was clearly impressed by Rentmeester’s photograph. Nike obtained a very limited license for it. But I’m guessing the photograph wasn’t exactly what Nike wanted for its advertisement campaign. So it shot its own:

Jordan’s pose is very similar, but not exactly the same. His legs are completely straight, and the toes of the trailing leg point backward, and his hips are (as a result) open. In Rentmeester’s photograph, his trailing leg is slightly bent in a running pose, and Jordan’s hips are closed. I’m guessing that in the Rentmeester shoot, Jordan was actually running toward the basket, whereas in the Nike shoot, he leapt straight up. The feeling that Jordan is heading toward the basket in the Nike photograph is, I think, an illusion caused by the way he stretches the ball toward the basket.

Rentmeester sued Nike10He waited a LONG time to do so. Nike took the photograph in 1985, then obtained a two-year license from Rentmeester, but kept using the photograph afterwards, so Rentmeester’s claim is over 30 years old. His damages, therefore, are limited to just the three years before his suit. and lost. The decision is here.

The Ninth Circuit pointed out that Rentmeester can’t claim ownership of the idea of a basketball player—or even a specific basketball player—performing a grande jetè with a basketball stretched toward the basket. This is so even though he idea is highly original. He can only claim ownership of how he captured that pose on film. It left open the possibility, however, that Nike could have infringed Rentmeester’s copyright if Jordan’s pose had been much more similar, even with all the differences in background, lighting, etc. Such was the power of the originality in Rentmeester’s posing of Jordan, according to the Ninth Circuit.

Oscar Michael Wilde Jordan

Jumping back to our hypothetical with Oscar Wilde, we decided that even a “normal” scène-à-faire pose can be protectable if you add enough original details to it. Here we have a highly original pose, but it seems Rentmeester is in the same boat as our hypothetical: subtract the gross pose and focus on the details. Rentmeester doesn’t seem to be getting credit for his originality.

One difference between a sitting pose and the Rentmeester-Jordan pose might be that a sitting pose can never be protectable, and the details we’re concerned about must be additions to the pose, not the minor articulations within it. Or, at least, the original articulations are so detailed and so minor that no model, no matter how talented, could exactly reproduce them. By contrast, the Ninth Circuit allows for the possibility, at least, that you really could infringe the Rentmeester-Jordan pose, perhaps if the hips remained closed and the trailing leg was bent. It’s just that Nike didn’t quite take enough of the pose for the issue to even go to a jury.11Upon some reflection, I think this analysis is missing an important point. The sitting pose and the Rentmeester-Jordan pose suffer from different types of unprotectability (is that even a word?). The sitting pose is a scène à faire, which is based on the idea that, if everyone in your field does it, it’s not really original. The Jordan pose is abstract. It is important that copyright not protect ideas. Protecting ideas is what patent is for, and regulating ideas would interfere with the right of free expression. It’s possible that, either way, we end up in the same place: thin protection for poses.

Think of it this way: If a jury did find Nike had infringed, what would you say was the extent of Rentmeester’s originality? Did he own any pose in which the subject did something like a grande jetè while extending a basketball upward and forward? That seems to be the sort of result the Ninth Circuit didn’t want to tolerate.

Still, one wishes Rentmeester got something out all of this. But that’s a problem with copyright: there really isn’t such a thing as a little bit of infringement. Either Rentmeester was going to get very rich, or he was going to get nothing.

Sorry, Not a Dol-Fan of This One

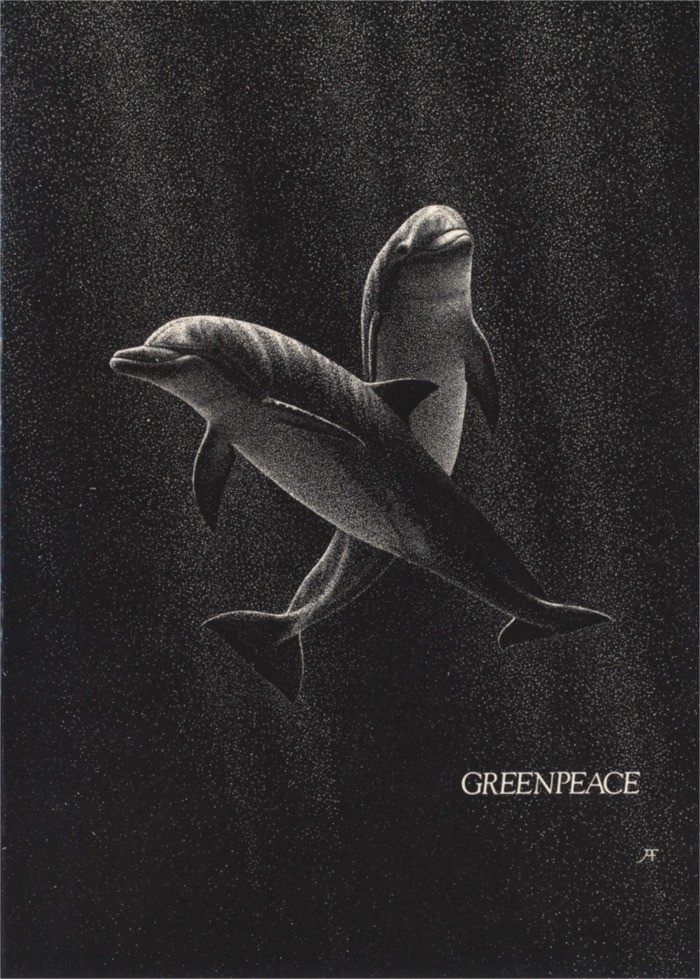

But, hold on, because Rentmeester v. Nike isn’t even the weirdest case involving the copyrightability of poses to be decided by the Ninth Circuit in the last six weeks! The next case, Folkens v. Wyland Worldwide, involves dolphins. The plaintiff made the following pen-and-ink drawing of two dolphins crossing at roughly their respective midpoints.The one behind curves upward and faces the viewer, while the one in front is straighter and is shown in profile:

Note that there isn’t a background for the dolphins.

Later, the defendant made the following painting, featuring dolphins crossing at roughly their midpoints, with the one in back curving and facing the view and the one in front straighter and in profile.

There’s a lot of other stuff in the painting, but it shouldn’t matter. The lighting might matter in other circumstances, but here it doesn’t because the dolphins are being depicted in the daytime and light must naturally filter down from above.

The dolphins look a lot alike. They appear to be the same species of dolphin (or, at least, their markings are the same), among other things. But they aren’t precisely alike. In the painting, the one in back is turned slightly away and thus twists less. The one in front has moved forward enough that its dorsal fin has cleared the other dolphin, and its tail points down instead of straight out. There are differences in the physical makeup of the dolphins’ bodies, which I attribute to the plaintiff’s superior familiarity with dolphins.12I’m no expert, obviously, but the plaintiff’s dolphins look a lot more like dolphins than the defendant’s.

We are thus presented with the same problem as in Rentmeester v. Nike: an artist has chosen to pose his subjects in an aesthetically pleasing way, rather than in a conventional (scène-à-faire) way. The Ninth Circuit reaches the same result, but in a very different—and very strange—way.

The Ninth Circuit decided that this case had nothing to do with posing and everything to do with whether the crossing of two dolphins was “first expressed in nature” and are thus “the common heritage of humankind, and not artist may copyright law to prevent others from depicting them.” The court was influenced by Satava v. Lowry, a case about glass sculptures of jellyfish encased in more glass. In Satava, the plaintiff really was arguing he had copyright protection over any naturalistic depiction of jellyfish encased in glass. The court there correctly told him that he couldn’t. Jellyfish exist in nature, and the parties’ depictions were naturalistic—i.e., meant to duplicate what is found in nature. Once you removed that, you were left with pretty different sculptures. The jellyfish look pretty different, their tendrils fall differently, and so forth.

With the dolphins, the Ninth Circuit doesn’t just eliminate the naturalistic depiction of dolphins, because there’s still the matter of how the plaintiff posed the dolphins. The court appears to believe that, given enough time, and enough hypothetical underwater observers around the world, eventually one hypothetical observer would see two dolphins crossing the way the plaintiff depicted the dolphins. So the Ninth Circuit eliminates any positioning of the two dolphins that might conceivably be observed in nature.

Consider the Majestic Moose

This takes Satava way, way, way too far. Consider the following less silly hypothetical. You are a nature photographer. You ensconce yourself in an advantageous spot, set up your equipment and wait, camera ready. Then you see whatever it is you’ve been waiting for. Perhaps it is the majestic moose. There are two of them, and they browse around for a while. You start snapping. Sometimes the moose are positioned in a dull, ordinary way, but sometimes they are positioned in aesthetically interesting ways. You’re good at what you do, and you snap pictures at the most interesting moments.

You publish the best of these photographs. Some painter, wishing to add moose in a larger nature scene, sees your photograph and depicts the moose almost exactly as they are in the photograph. You had no control over exactly what the moose looked like, so that’s not protectable. But you were able to choose what position the moose would be in. You didn’t have absolute control, of course, but you chose to take pictures at some times and not at others.

I am to understand, based on Folkens, that the painter isn’t infringing on my copyright because my copyright is “thin” and covers only precise duplications. As wrong as I think that is, I think it can get worse. Consider that the plaintiff in Folkens either posed the dolphins (somehow) or imagined the pose. This is to say, he had a much wider range of creative choice than you had with the moose, where you were stuck with whatever the moose did, from the vantage point you chose. If Folkens’ copyright in the crossing dolphins is thin, then what do you have in the browsing majestic moose? Even thinner somehow? None at all?

Of course, Folkens and Rentmeester ended up in the same place: poses are protectable, but the protection is thin. It appears not to matter whether the posing was intentional or not, or whether it is conventional or not, or whether it’s in a photograph or not. If that’s the rule, fine. At least is an easily understood rule. But I think the rule sells some artists short.

I can’t help but conclude that Rentmeester is probably correctly decided. As much as one might wish, copyright doesn’t protect clever ideas, and Nike worked around the protectable elements. But Folkens is surely wrong: the question of infringement should have gone to a jury.13Note that the plaintiff must still prove access, which was not at issue. The painting’s depiction of the dolphins is not quite exact, but it’s very close. Even after you subtract the natural facts that dolphins look certain way and move a certain way, the painting takes nearly everything left over. At minimum, the pose should have been in the calculation of whether too much was appropriated.

Finally, for a different analysis of the Rentmeester and Folkens decisions, take a look at the Written Description blog.

Thanks for reading!

Footnotes

| ↑1 | The “Napoleon” of Broadway photography. Sorry. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The copyright act in force at the time specified photographs as protectable, but many felt that the inclusion was unconstitutional, on grounds that photographers aren’t “authors.” |

| ↑3 | Who was the defendant in the case. No, he didn’t sue himself. He sold the copyright in “Grace of Youth” then tried to re-create the pose and got sued by the new owner of the copyright in “Grace of Youth.” |

| ↑4 | Or maybe she can’t help it. She’s got a cherry stem between her teeth. |

| ↑5 | Let us put aside the equally fascinating question of whether the first photographer has a separate copyright in a sculptural work, and that the second one infringed that copyright even before he took the photograph. |

| ↑6 | A term borrowed from stagecraft and playwriting, which referred to stage conventions so powerful that playwrights couldn’t ignore them. The term is obviously expanded in a couple dimensions for use in copyright law. |

| ↑7 | Don’t be fooled by my repetition of “stock.” Stock photography isn’t a scène à faire, for example. |

| ↑8 | It isn’t. |

| ↑9 | Your skin might be a tangible medium of expression, i.e., for tattoos, but your body overall isn’t. |

| ↑10 | He waited a LONG time to do so. Nike took the photograph in 1985, then obtained a two-year license from Rentmeester, but kept using the photograph afterwards, so Rentmeester’s claim is over 30 years old. His damages, therefore, are limited to just the three years before his suit. |

| ↑11 | Upon some reflection, I think this analysis is missing an important point. The sitting pose and the Rentmeester-Jordan pose suffer from different types of unprotectability (is that even a word?). The sitting pose is a scène à faire, which is based on the idea that, if everyone in your field does it, it’s not really original. The Jordan pose is abstract. It is important that copyright not protect ideas. Protecting ideas is what patent is for, and regulating ideas would interfere with the right of free expression. It’s possible that, either way, we end up in the same place: thin protection for poses. |

| ↑12 | I’m no expert, obviously, but the plaintiff’s dolphins look a lot more like dolphins than the defendant’s. |

| ↑13 | Note that the plaintiff must still prove access, which was not at issue. |

But was the dolphin depiction COPIED? Is this yet not the key issue?

In the case of the posed lady, we know the artist had prior knowledge of the photo because he took it himself. He copied.

Wilde, and I suppose this portrait, were famous. Literal copying might be deduced.

But in the case of the dolphins, surely the question of whether there was literal copying is a question worthy of mention?

Thanks for the great presentation, as always!

Agreed. In the crossing-dolphins case, the defendants assumed access for purposes of summary judgment only, so access/copying wasn’t at issue (which also means no one had a need to argue striking similarity). That sort of implies that access wasn’t very cut-and-dried. But isn’t it kind of telling that we’re really interested in the access/copying question? It means we really believe the similarities are substantial enough to go to a jury.