Does Distributing a Work Under Creative Commons Mean That Your Work Has No Economic Value?

A professional photographer finds a political website has used his photographs of celebrities in concert to show that the celebrities agree with the website’s viewpoint. He licensed the photographs under Creative Commons, but the website violated the terms. Can the website escape under fair use?

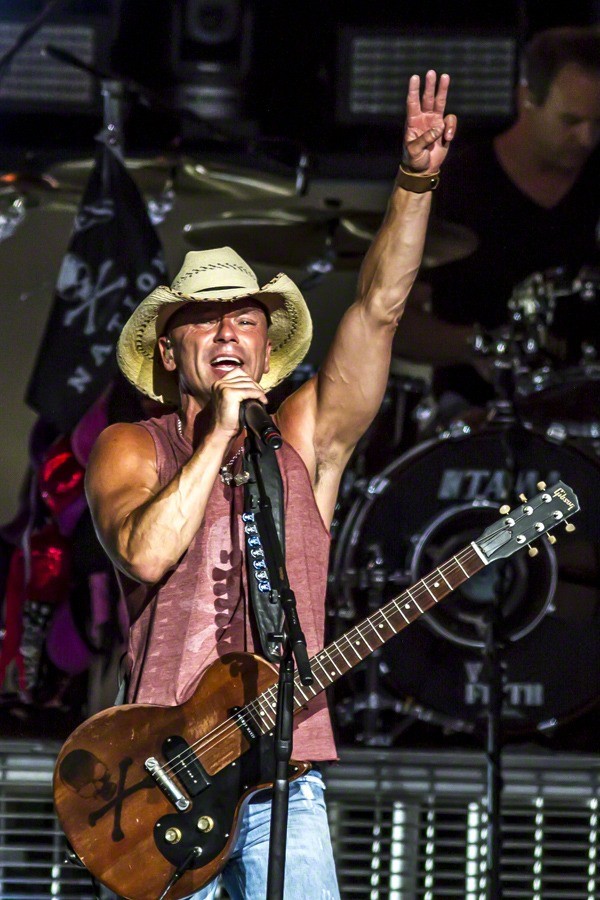

The plaintiff is a photographer. He took this photograph of Kenny Chesney 1For those of you who aren’t fans of country music, Kenny Chesney is a big deal. performing in concert:

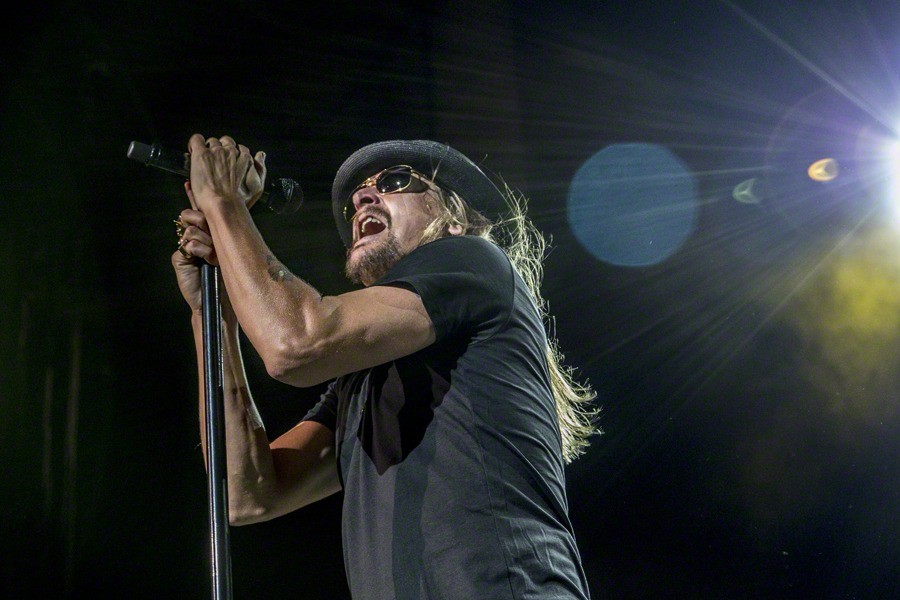

And this photograph of Kid Rock2I know you know that Kid Rock is a big deal, though do any of you know why? I sure don’t. performing in concert:

Although the plaintiff is a professional (which is evident from the quality of the photography), he decided to upload these photographs to Wikimedia under the Creative Commons attribution license (the “CCL”). Anyone may use the photographs for any purpose, without payment of any kind, so long as the photographer gets credit for it. The photographer says he uses CCL for marketing purposes and is, thus, valuable to him.

The defendant is non-profit that promotes a certain religious-political belief. I’m not going to tell you what it is because it’s irrelevant. The non-profit wanted to tell the world, through its website, that Kenny Chesney and Kid Rock also share this belief3Based on slim evidence, to be honest.. To make the webpage look better (or perhaps more persuasive), the non-profit wanted to include photographs of Kenny Chesney and Kid Rock. Any they came across the plaintiff’s two photographs, downloaded them and put them in the webpage about Kenny Chesney and Kid Rock. Naturally, the they didn’t attribute the photographs to the plaintiff.4Sometimes I really question the value of the attribution. Often, the photographer’s identity is just a username, so you end up saying, “Photography by QbertLover.” Even when you know the photographer’s name, the name is pretty much meaningless as marketing if it lacks contact information. Here, at least, the photographer was clear about how he wanted his work attributed.

The non-profit has advertising on the webpage featuring the photographs and earned $16.68 from it. It also solicits donations, receiving $50.00 (not a typo) during a three-month period.

The photographer found out about how the non-profit was using his photographs and sued. Since he doesn’t make money (directly) from uses of the photographs, one might fairly speculate about his motivations. Though the court’s opinion doesn’t say so, I’m guessing he disagrees with the non-profit’s point of view and didn’t want his photographs associated with this point of view. I recognize a flaw in my reasoning: since the non-profit didn’t attribute the photographs to the plaintiff, the link between the website and the photographer isn’t very obvious. Maybe the plaintiff was just concerned his friends would recognize his work and think, “Oh my! Does he support [undisclosed viewpoint]?”5Alternatively, maybe the photographer just sees an easy payday, because he is entitled to statutory damages of $750 to $30,000, and maybe up to $150,000 if the infringement is willful. Under the circumstances, I can’t imagine a jury going much above the minimum here.

Updated 1-23-18: Nope, my speculation here is probably wrong. I plugged the plaintiff’s name into PACER as a plaintiff in copyright cases, and I found quite a number. There were 59 hits, none filed any earlier than 2014, the most recent filed last Friday. Some are going to be duplicates (e.g., same case filed in different courts), but this photographer has been busy. There is also no ideological pattern. They seem mostly (but not always) to settle.

The first hurdle the photographer had to clear was that CCL business. He did, after all, license the photographs to all comers, including ones he didn’t like. Luckily, the non-profit didn’t attribute the photographs to him.6And, just a luckily, no one just reading the webpage knew he had taken them. Um, wait.The court ruled that, under the CCL’s terms, the license terminated at that point.

The next hurdle was whether the non-profit’s use of the photographs was fair. What do you think? Before you decide, be sure to review the four fair-use factors.

But wait! Before you decide, consider the two leading fair-use cases in the court’s Circuit. Coincidentally, I’ve blogged about them before! They involve the old Baltimore Ravens’ “wingèd shield” logo. The Fourth Circuit held that showing the old logo in old highlight films (inevitable because the logo was painted prominently on Baltimore’s field) was not transformative and (thus) not fair use. But the use in a small museum-like display, maintained by the team in its stadium, was transformative and (thus) was fair use. I’ll give you a hint: the court here thinks the non-profit’s use of the photographs is a lot more like one of these cases than the other—but I won’t tell you which one!

Have you made your guess? Be prepared for disappointment and click here for the answer.

Updated 1-20-18 to straighten out some mixed-up “nots” in the final substantive paragraph.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | For those of you who aren’t fans of country music, Kenny Chesney is a big deal. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | I know you know that Kid Rock is a big deal, though do any of you know why? I sure don’t. |

| ↑3 | Based on slim evidence, to be honest. |

| ↑4 | Sometimes I really question the value of the attribution. Often, the photographer’s identity is just a username, so you end up saying, “Photography by QbertLover.” Even when you know the photographer’s name, the name is pretty much meaningless as marketing if it lacks contact information. Here, at least, the photographer was clear about how he wanted his work attributed. |

| ↑5 | Alternatively, maybe the photographer just sees an easy payday, because he is entitled to statutory damages of $750 to $30,000, and maybe up to $150,000 if the infringement is willful. Under the circumstances, I can’t imagine a jury going much above the minimum here. |

| ↑6 | And, just a luckily, no one just reading the webpage knew he had taken them. Um, wait. |