When 330,000 Yards of Lace Still Isn’t Enough

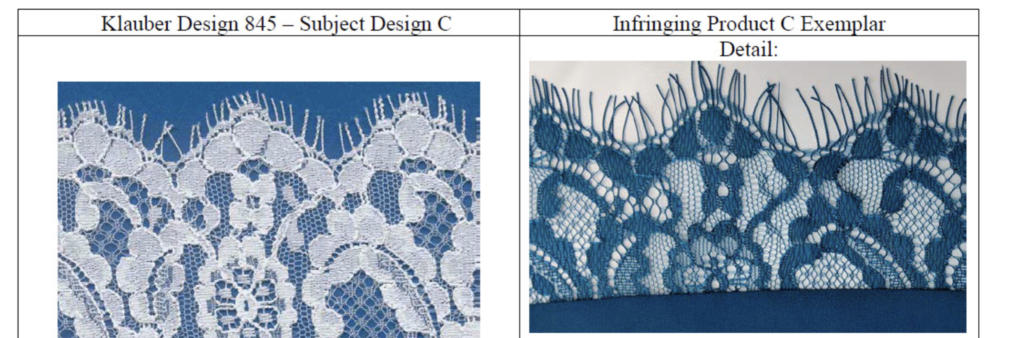

This is a copyright case involving lace designs. Yes, lace designs. Have I mentioned before the tremendous breadth of the subject matter of copyright? The same law that protects “Thank You, Next” and random medical brochures in your physician’s waiting room also covers lace. Here are the two designs I want to discuss, with the accused design on the right and the asserted design on the left.

They look pretty similar, no?

The case is a copyright dispute between The Dress Barn, which is apparently some sort of New England phenomena, and Klauber Brothers “rigid and stretch laces since 1859.”

In some strongly-worded demand letters, Klauber Brothers accused The Dress Barn of copying its copyrighted lace designs. Rather than argue the point, The Dress Barn sued Klauber Brothers for a declaration that its dresses did not infringe Klauber Brothers’ lace designs. Because Klauber Brothers is based in New York City, The Dress Barn sued there. The Southern District of New York is not a friendly venue for copyright claimants, so even though The Dress Barn wasn’t in a “home” venue, it was in a good venue for the party being accused of infringement.

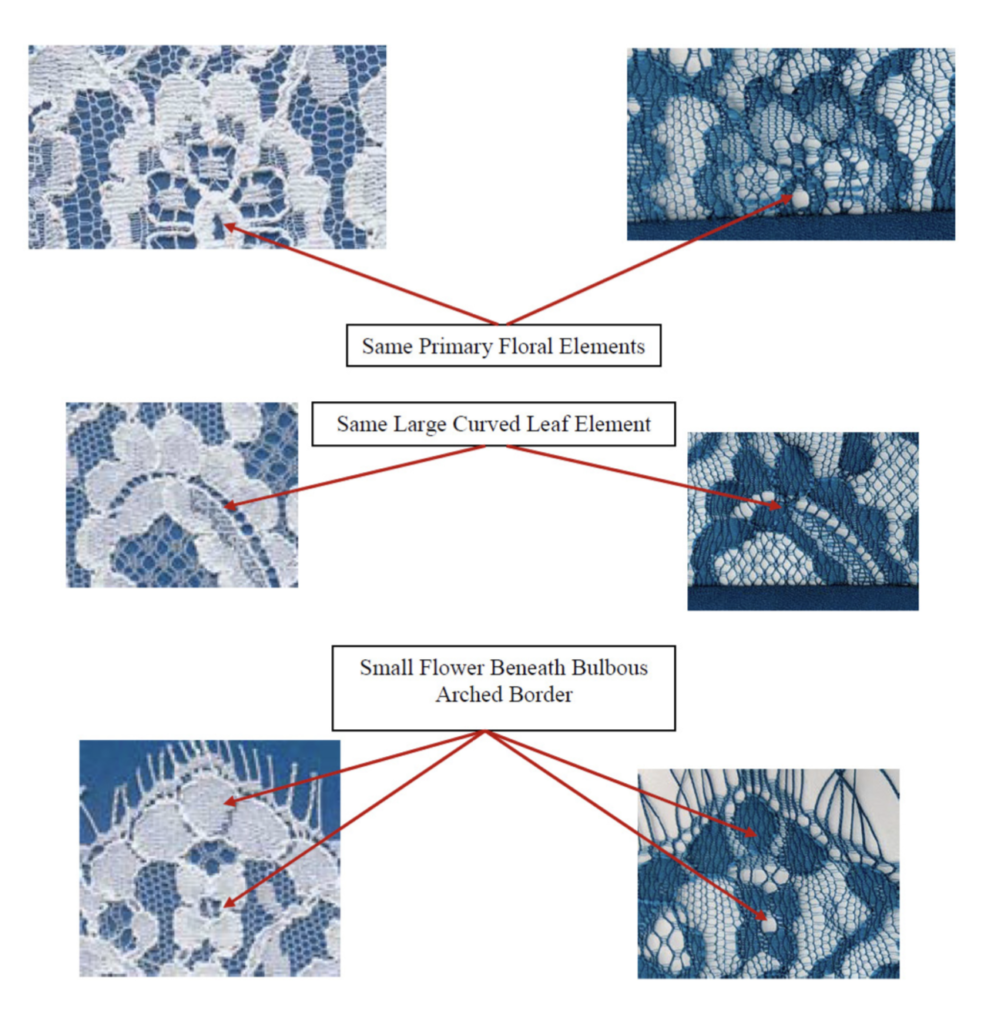

Klauber Brothers had no choice but to bring a counterclaim for copyright infringement1If it hadn’t, it would have waived its claim for copyright infringement claims, even if it had prevailed on the declaratory claim. That’s something to remember when bringing declaratory actions: it almost guarantees that you’ll face the exact substantive claim that you’re seeking a declaration about. So don’t do it lightly.. It claimed infringement of two lace designs. One of them really wasn’t very similar, but the other—the one illustrated above—is very similar. Klauber Brothers even provided this handy diagram pointing out the similarities, just in case they weren’t obvious.

Wisely, The Dress Barn didn’t challenge similarity. It challenged challenging access.

The Kind of Access You Don’t Want

Now, under the traditional framework for copyright infringement, the copyright holder must normally prove (a) access and (b) “substantial similarity.” The idea—the completely correct idea—is that you can’t have copied something if you didn’t even have access to it. So we usually call on the copyright owner to prove some connection between the defendant’s creation of the allegedly infringing work and the copyrighted work.

There’s something of an exception to this: “striking similarity.” The two works are so similar that copying is the only explanation. If the accused infringer were in possession of hundreds of photocopies of a chapter of a textbook, you shouldn’t have to prove access. There’s no way the defendant could’ve made the photocopies without the textbook.

In this case, Klauber Brothers didn’t allege any direct evidence of access. I.e., it couldn’t truthfully say for sure that The Dress Barn had actually come into possession of a sample of the lace design. How could it, without inside information? No fear. It’s fairly normal to allege access indirectly. For example, you might be able to allege that you definitely gave a lace sample to someone who has some relationship with The Dress Barn, and suggest that that’s how it got into The Dress Barn’s possession.

But Klauber Brothers couldn’t truthfully allege anything like that. Instead, it based its theory of access on widespread dissemination. This is a fairly common type of access. The classic examples are popular music or movies. You can allege that a very large number of people heard or saw the work. And, in the case of music, you can allege that even more people overheard the music (on the radio, in shops, etc.). And it’s plausible that someone connected with the accused infringer heard or saw the music.

With physical goods, the concept isn’t much different. You need to allege that lots of people have come into possession of the copyrighted items, either because you directly gave it to them, or because you gave it someone who then distributed the goods widely. But you do need to orient your allegations to access. If the accused infringer is based in Oregon but your goods are distributed mostly in Florida, your distribution might be widespread, but it’s not widespread in the right place.

And that’s where Klauber Brothers ran into a spot of trouble. It alleged only that it had distributed 330,000 yards of the copyrighted cloth—which is a lot—to “numerous parties in the fashion and apparel industries.” Klauber Brothers appeared to assume that, with that much cloth placed that firmly into the industry’s stream of commerce, some of it would inevitably have wound up in the hands of The Dress Barn. And you know what? I think a lot of courts would have agreed. But not this one. This one wanted to know more about where and when the 330,000 yards was distributed. And I think it also wanted to know (without quite saying so explicitly) how the cloth might have wound up at The Dress Barn, other than just through the magic of commerce streams.

Close Only Counts in Horseshoes and Hand Grenades (and Copying)

Klauber Brothers then argued for “striking similarity.” But the court—correctly, in my view—felt that they weren’t quite similar enough. If you didn’t know anything else, not even about the 330,000 yards of cloth, but only could rely on the copyrighted lace and the accused lace, would you say: there’s no way the accused lace looks like that unless The Dress Barn copied the copyrighted lace?

But wait: you do know more than that. And I think here the court’s analysis fails. Striking similarity isn’t really an exception to access. It’s one extreme of the balance between access and “probative” similarity. Probative similarity is crucially different from substantial similarity. Substantial similarity measures whether what you took was wrong (i.e., you took too much of the wrong things). But probative similarity measures whether you copied at all. I explain how this works in this Techdirt article, and elsewhere in this blog, especially here.

If you combine the high degree of similarity with the 330,000 yards, I think you have to conclude that Klauber Brothers has alleged enough for access, at least at this early stage in the lawsuit.

But it’s not a disaster for Klauber Brothers, because when a complaint (or counterclaim) is rejected because the court didn’t find quite enough allegations to support the claim, the court will give the claimant a chance to add more allegations to get over the hump. If the claimant can, then the case proceeds. If the claimant can’t, then case over.

This court, shockingly, denied Klauber Brothers this opportunity. Klauber Brothers had amended its counterclaim once, and after The Dress Barn moved to dismiss the amended counterclaim, the court warned Klauber Brothers that it wouldn’t permit an amendment after it ruled on the motion, but it gave Klauber Brothers an opportunity to amend a second time while the motion was still pending. Klauber Brothers chose to stand on its current counterclaim, and the judge is sticking to her warning. Although judges have wide discretion to manage their dockets, they may not work an injustice to do so.

Now, you might be wondering whether the Klauber Brothers lace design is protectable. You’ve seen a lot of lace in your life, and honestly, that design just looks like different lace features thrown together in a not-very-interesting way. My response is: maybe you’re right! But it’s too early to determine that. To determine whether the copyrighted design was just a bunch of scènes à faire (lace equivalent thereof), we’d need to know a lot more about lace designs, what other lace designers thinks are common designs and so forth. That’s right: it means lace experts!

Anyway, at this stage, all we have are the allegations in the amended counterclaim and Klauber Brothers’ copyright registration. The registration2If obtained within five years of publication! means that Klauber Brothers doesn’t have to prove the design is protectable, but rather the burden is on The Dress Barn to prove the design isn’t protectable.

Thanks for reading!

Footnotes

| ↑1 | If it hadn’t, it would have waived its claim for copyright infringement claims, even if it had prevailed on the declaratory claim. That’s something to remember when bringing declaratory actions: it almost guarantees that you’ll face the exact substantive claim that you’re seeking a declaration about. So don’t do it lightly. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | If obtained within five years of publication! |