What a Fight Between Two Lines of Stuffed Animals Teaches Us About Trade Dress and Functionality

I’ve warned you about trying to protect “designs” in the U.S. before. Outside of design patents (which are rare and not always an option), U.S. law doesn’t really recognize “designs.” It recognizes sculptures (under copyright law) and trade dress (under trademark law). Both have their limitations.

Let’s say you want to protect this “design”:

A single Squishmallow, downloaded from Squishmallows.com

Copyright would absolutely protect this! Of course, we’d have to debate how much it would protect—the “thickness” of the protection. If someone made their own leg-less egg-shaped cat, you probably couldn’t stop them. The protection isn’t that “thick.”

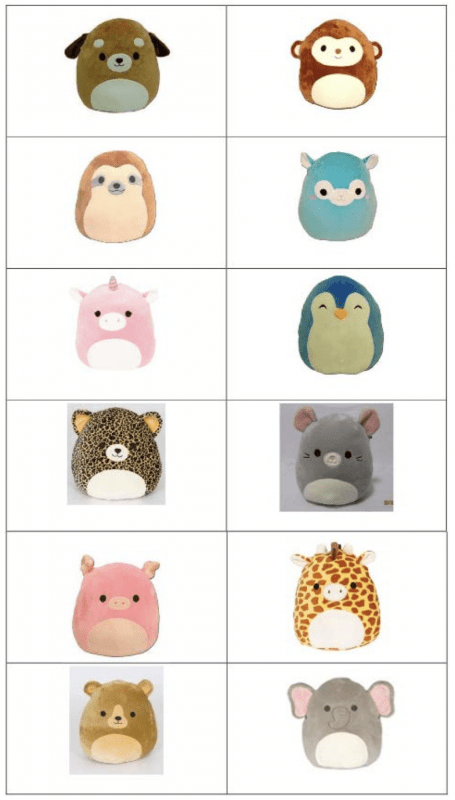

Besides, what you really want to protect is a line of products, like these:

A group of Squishmallows (from the court opinion)

Here, trademark can be your friend. Trademark law will protect common elements in a line of closely related products. If you think about, you’ll realize you see this all the time. This logic applies to trade dress.

Now Entering Realm of Trademark

But now we’re in the realm of trademark law. That means we aren’t protecting “designs.” We’re protecting consumers’ responses to designs. This means the rights don’t arise when you make the design (or set of designs), as with copyright. They arise when consumers start associating the design with the source of the product line. Somewhere, deep in the consumers’ minds, there needs to be a thought along the lines of: “Oh, hey, I recognize that design, and I like/trust whoever makes those products.”

Go back and look at the range of the products above. What would you say is distinctive about them? Egg-shaped; of a certain size, fuzzy; flat noses but articulated ears and horns; lack of limbs; and black, beady, oval-shaped1Always? Some seem round. The bird’s eyes are really out of order, though., fabric eyes.

But, when we apply trademark law to product design, we are subject to certain limitations. The first is that the features that we claim to be distinctive are not also functional. The reason for this rule is to keep trademark law and patent law separate.2Because trademark rights last as long as they are remain used in commerce, but patent rights last for a relatively short period of time, we don’t want to give trademark-like rights to useful features. Thus, even if your design is distinctive and acts as a trademark, the law won’t protect it if it’s also functional. The result could be kind of heartbreaking: all that goodwill for nothing.

Functionality Can Be Huggable

But what’s functional about a bunch of squishy stuff animals? Well, squishiness, for one thing. Children like to hug their stuffed animals. The same goes to the fuzziness: just nicer to hug. This also applies to the size: just right for small children to hug. This might also go to the peculiar shape. There’s just more to hug.

What about the noses? The ears and horns are articulated but not the noses. The noses are flat, even when the animal being depicted actually has a sizable snout. Unicorns, for example, are well-documented as having very large, long noses. Heck, their faces are almost all nose. But here, it’s just a flat white fabric oval with two smaller pink ovals representing nostrils.

The reason for this is that these stuffed animals are designed to be used as pillows. Children often use their stuffed animals as impromptu pillows, so why not just make the stuffed animal into a pillow? You can see how the nose can’t stick out. You can also see why the eyes have to be fabric, and why the stuff animals have to be round.

Why are they egg-shaped? So they can stand up

That peculiar shape might also go to cost. Remember ratio of volume to surface area from science class? Spherical objects maximize volume to surface area. This means you have the largest stuffed animal for the least amount of fabric. Assuming the fabric costs more than the stuffing, that would make them cheaper to make, especially when you get rid of those pesky arms, legs and tails.

Imitation Might Not Be Flattering, But It Might Not Be Illegal, Either

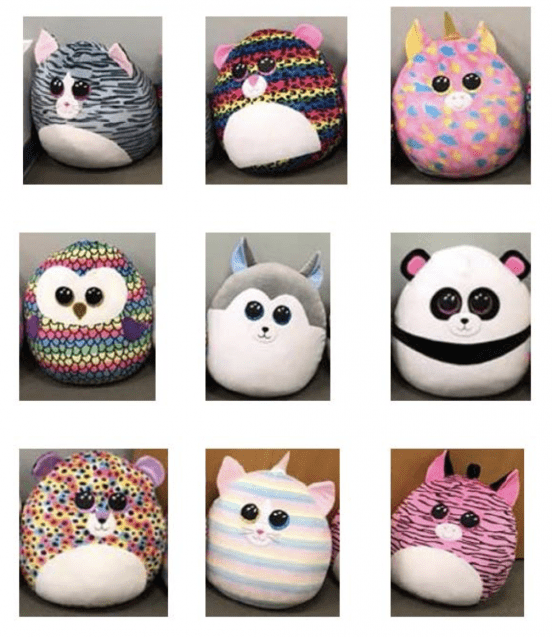

So, now one of your competitors are making these:

A group of Squish-a-Boos (from the court opinion)

(Better images found here.) They are obviously copying your design. These are fuzzy, squishy, egg-shaped stuffed animals with articulated ears and horns but flat noses, of a certain size. So you sue, right?

That’s what happened in KellyToy Worldwide v. Ty, Inc. KellyToys developed, manufactures and sells the beady-eyed egg-shaped stuffed animals, pictured at the beginning of this post. They’re called “Squishmallows.” I’m familiar with them because one of my children owns one (pictured at the end of the post). Ty is well-known for Beanie Babies, of course, which nearly destroyed the republic in the 1990s.

KellyToys moved for a preliminary injunction to stop Ty from selling the Squish-a-Boos. The motion was denied.

But the problem is, there isn’t much left to KellyToy’s claimed trade dress after you’ve accounted for all the functional bits. Ty isn’t so much trading on KellyToy’s goodwill as much as it saw a good idea and went with it. If your goodwill is bound up in that unprotectable idea, well, too bad.

Not Very Confusing

There was another problem with KellyToy’s case: likelihood of confusion. Although we think we’re protecting a “design,” we’re really protecting a kind of trademark, and that always, always means proving that consumers are likely to be confused into thinking the two “designs” represent a single source for both product lines. And, here, even if you assume that the product design really is protectable as trade dress, the Squish-a-Boos look pretty different from the Squishmallows: the eyes. Those great, staring, unblinking, colorful, plastic eyes.

Ty already has a successful line of stuffed animals called “Beanie-Boos.” They’re like the famous “Beanie-Baby” stuffed animals, but they have these great, staring, unblinking, colorful, plastic eyes. Below is a photograph of, left to right, (1) a Beanie-Boo cat3Again, this isn’t the allegedly infringing products. It’s here to show what the eyes look like in a different context., (2) a Squishmallow cat, and (3) a real cat (for comparison):

Beanie Boo cat (L), Squishmallow cat (C), and real cat (R) for comparison. Picture taken with permission of its subject, Ivy Minerva “Skittles” Scout Fuzzytummy Scytheclaw

So, when I see a “Squish-a-Boo,” I don’t so much recognize the various elements of the Squishmallow trade dress (with which I am familiar), so much as I immediately recognize those great, staring, unblinking, colorful plastic eyes. And I immediately connect the Squish-a-Boos with Beanie Boos as having the same source.

On top of that (and this was more significant to the court), Ty sells its products with a heart-shaped tag, which is extremely famous, since it goes back to the Beanie-Baby days. Either way, the court believed that consumers wouldn’t likely be confused for long (if they’re confused at all) because the Squish-a-Boos have their own distinguishing characteristics.

Squishmallows Didn’t Win the Motion, But They Won My Heart

Having said that, given a choice between Squishmallows and Squish-a-Boos, I’d choose the Squishmallow. The problem with the Squish-a-Boos’ eyes is that they’re big and made out of hard plastic. That makes the stuffed animal a lot less comfortable as a pillow.

P.S. Oddly, this is the second blog post I’ve written this year about “squishy” or “squeeze-y” stuffed animal. I wrote this one about “Squeezamals” and copyright registration problems in July.

Thanks for reading!

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Always? Some seem round. The bird’s eyes are really out of order, though. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Because trademark rights last as long as they are remain used in commerce, but patent rights last for a relatively short period of time, we don’t want to give trademark-like rights to useful features. |

| ↑3 | Again, this isn’t the allegedly infringing products. It’s here to show what the eyes look like in a different context. |