Intellectual Property and Personal Property: Two Great Tastes That Might Not Taste Great Together

When everything runs on software, then everything will be subject to copyright protection, and you might not like the consequences.1OK, this is an overgeneralization, but not as much of one as one might hope, as I hope you’ll see. Let’s take cars, for example. In the old days, if your car needed a new distributor cap, you’d go down the neighborhood auto supply shop, and you would have several different manufacturers competing for your money, which keeps the price for replacement parts low. One of the manufacturers might be “authorized” by the car manufacturer and appropriately branded. And that one might command a somewhat higher price because of that association and the sense that it will somehow work better with your car. That premium is the result of branding—and trademark law—and years of hard work building up the brand.

The Right to Distribute Distributors

Slap a little computer module on the distributor cap, and the car manufacturer has a lot more control over who can manufacture replacement distributor caps. That’s because the computer module requires software, and software is made up of characters, and that makes it a literary work that is subject to copyright protection. It doesn’t matter if the only characters involved are 0 and 1, or if only a computer can read it. The rights to make copies of the software, or to distribute physical goods holding copies of the software2Distribution, like reproduction, is another exclusive copyright right. It’s the right to give out—by sale, by rent, or just for kicks—physical goods that contain the copyrighted work. Normally, these take the form of books, CDs and the like, but there’s no reason it can’t include modules. Or the entire car., are now limited by the manufacturer, who can license those rights as much or as little as it wants. It can choose to license the software to nobody and establish a monopoly over the right to make and sell our computerized distributor cap. If a competitor wishes to make and sell unauthorized replacement computerized distributor caps, the car manufacture can sue to stop it. You’ll pay more for the caps—and not just because of the little computer module—but because there will be less competition.

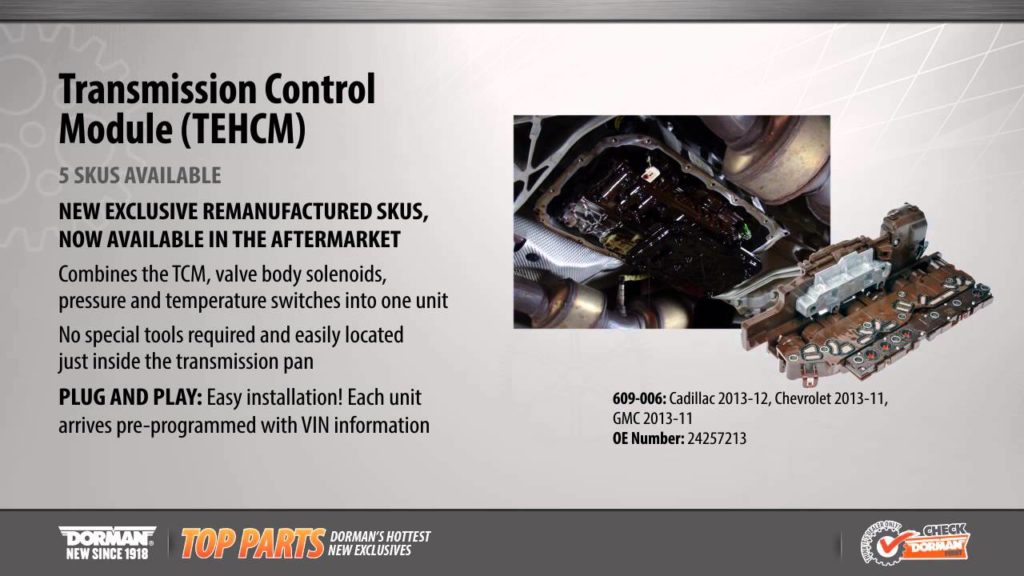

Replace “computerized distributor cap” with “Transmission Electro-Hydraulic Control Module or TEHCM,” and that’s pretty much what GM is trying to do to two aftermarket automotive parts suppliers. In its complaint, GM alleges that the defendant retailers are taking “blank” modules, programming them to work with GM’s cars, and selling them. It’s not clear how the defendants are programming the modules, but it’s at least possible that they somehow got ahold of a copy of the program and are using that.3If the defendants simply coded their own software to perform the module’s necessary functions, then GM’s copyright claims would fail then and there because there would be no copying. If all this is true—and at this stage, they’re just allegations—not only could GM stop them from making and selling the modules, but it could impound all the ones that have already been manufactured and destroy them.

GM doesn’t maintain a monopoly over the software (though it could). It has a subscription program that allows repairs shops to program and re-program GM modules, including the TEHCMs. GM says it does this not for the money but for the customer’s benefit: the customer can be assured that the module will have the most recent version of the software.4This can’t be that important. We drive cars for years without updating the software in our cars’ various computer modules. I don’t know if I’ve ever heard of a critical software update for a car, though that day can’t be too far off. Whether this is true or not, I’m pretty sure GM does it for the money, too.

Locking the Gate Before the Horse Is in the Paddock

GM didn’t just just sue for copyright infringement. It also sued under the anti-circumvention provisions of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA). Readers of this blog are used to seeing the DMCA in the context of safe harbors against copyright infringement, but the DMCA also made it illegal to circumvent “technological measures” that prevent access to a copyrighted work—such as the code on the modules. In order to program the modules, according to GM, the defendants had to circumvent some sort of “software lock.” Read that last sentence twice, and you might see why, even based on my little thumbnail of DMCA anti-circumvention law, GM’s claim makes no sense.

The defendants brought a “Rule 12(b)(6) motion” to dismiss the case. In such a motion, everyone pretends that every fact alleged by GM in its complaint is true5Within reason. If your complaint is grounded on the allegation that pigs can fly, then, no., but even so, GM didn’t make a claim that it can win on.

Right off the bat, the DMCA claim is killed off (perhaps you saw that coming). The obvious problem is that the defendants weren’t circumventing the “software lock” to get at the juicy software inside, but in order to put software inside the module. The DMCA anti-circumvention provision basically says that if you build a fence around your horse, and put a cheap padlock on the gate, you can sue someone if they snap your cheap padlock and go into the enclosure with the horse.6Note to the analogy police: I don’t know what would happen if you just hopped the fence. Maybe this isn’t a perfect analogy. The bad guys don’t have to steal the horse or do mean things to the horse. Just being in there with the horse is enough. They could be feeding the horse sugar cubes and petting it softly on the nose. It doesn’t matter. But in this case, your fence encloses nothing, and the bad guys are snapping your cheap padlock so they can lead a horse into the enclosure. That’s not prohibited by the DMCA.7GM essentially tried to argue that, for the moment that the bad guys put the horse into the enclosure, they are briefly inside the enclosure with the horse. The court said, nice try: the horse has to be there first.

The copyright infringement claim is also thrown out, but this might be only a temporary setback for GM. GM’s problem is that it doesn’t know which software code is actually at issue, and so it can’t match the allegedly infringing software code up with any identifiable copyrighted computer program. This perhaps shouldn’t be too surprising a problem, when all of the software on all of GM’s modules consists of code that can be read only by machines. Unless GM kept really meticulous records, it might be difficult to know which registration goes with which module’s software.8GM also seems not to have done a very good job of obtaining copies of the allegedly infringing software, which shouldn’t be that hard: according to GM’s complaint, anyone can by the modules at issue online.

GM will get a chance to fix any problems with its complaint. While I think the DMCA claim is dead in the water, I suspect GM will get its act together enough to link a particular copyright registration to the software at issue. Then the real fun will start…

Software: Functionally Expressive, or Just Expressively Functional?

The real fun has to do with a limitation to the generalization I started this post with. Software code may be protected by copyright only to the extent it is expressive, and it is expressive only to the extent that it is more than merely functional. A lot of software code—perhaps most—is functional and thus outside the protection of software. That’s not as fatal as you might think, though. In any computer program, it is a safe bet that a little bit of the code is expressive. If you copy the entire program—essential if you want to use it—you’ll also copy that protectable bit, so you’re still and infringer.

It is possible, however, that programs at issue with these car modules are so short that they don’t contain any protectable code. But proving that will be a bear. You’ll need an expert—a pretty good expert9Being a good expert is more than just knowing stuff. It’s also being able to explain that stuff well to judges and juries and being likable and non-condescending while doing it. and hope you can explain the complexities of “abstract-filtration-comparison” well enough to the judge. If GM is your opponent, are you really going to be game for that? We’ll see if these defendants have the resources to beat GM, even if they have a winning case.10I’m leaving aside the very real possibility that the defendants aren’t even copying GM’s software because they commissioned someone to write a computer program, without reference to GM’s code, that performs the same functions. That would be a much easier defense because it’s really GM’s burden to prove copying. All the defendants need to do is watch GM’s tide dash against the looming cliffs.

What about fair use? The best fair-use argument I can think of is that it would prevent GM from extending a monopoly in software over products that are controlled by the software. This argument is appealing, but it doesn’t fit very well into the four fair-use factors.

- Nature of the use: It’s a commercial use (a point against fair use), and it’s “transformational” only in the fevered imaginings of some Second Circuit judges (this case is pending in the Sixth).11In fact, I don’t think it’s transformational, even in the broadest sense of that concept. The infringing software will do exactly what the copyrighted software does, in exactly the same context. Overall, I’d say this factor leans slightly against fair use.

- Nature of the copyrighted work: Software that you’d find on a car module isn’t going to be very expressive. This factor leans in favor of fair use.

- Amount and centrality of taking: I assume the entire code was taken. If so, this factor leans against fair use.

- Effect on market: GM actually has a subscription service for this software, so there’s an extant market that would be hurt by the defendant’s uses. This factor, it seems to me, weighs quite a bit against fair use.

In sum12The other defense that could be raised in this sort of situation is copyright misuse, which derives from antitrust law: you can’t use your (legal) copyright monopoly to gain a monopoly on things outside of copyright law’s purview. I’ve never seen is applied where, as here, the copyrighted material is fairly well integrated into the device. This is a far cry from stamping a tiny little copyrighted emblem onto a watch to control otherwise legal importation of the watch., unless the defendant commissioned someone to write software without reference to GM’s copyrighted code, the defendants’ best bet is to try to prove GM’s code is entirely devoid of expressive content.

Thanks for reading!

Footnotes

| ↑1 | OK, this is an overgeneralization, but not as much of one as one might hope, as I hope you’ll see. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Distribution, like reproduction, is another exclusive copyright right. It’s the right to give out—by sale, by rent, or just for kicks—physical goods that contain the copyrighted work. Normally, these take the form of books, CDs and the like, but there’s no reason it can’t include modules. Or the entire car. |

| ↑3 | If the defendants simply coded their own software to perform the module’s necessary functions, then GM’s copyright claims would fail then and there because there would be no copying. |

| ↑4 | This can’t be that important. We drive cars for years without updating the software in our cars’ various computer modules. I don’t know if I’ve ever heard of a critical software update for a car, though that day can’t be too far off. |

| ↑5 | Within reason. If your complaint is grounded on the allegation that pigs can fly, then, no. |

| ↑6 | Note to the analogy police: I don’t know what would happen if you just hopped the fence. Maybe this isn’t a perfect analogy. |

| ↑7 | GM essentially tried to argue that, for the moment that the bad guys put the horse into the enclosure, they are briefly inside the enclosure with the horse. The court said, nice try: the horse has to be there first. |

| ↑8 | GM also seems not to have done a very good job of obtaining copies of the allegedly infringing software, which shouldn’t be that hard: according to GM’s complaint, anyone can by the modules at issue online. |

| ↑9 | Being a good expert is more than just knowing stuff. It’s also being able to explain that stuff well to judges and juries and being likable and non-condescending while doing it. |

| ↑10 | I’m leaving aside the very real possibility that the defendants aren’t even copying GM’s software because they commissioned someone to write a computer program, without reference to GM’s code, that performs the same functions. That would be a much easier defense because it’s really GM’s burden to prove copying. All the defendants need to do is watch GM’s tide dash against the looming cliffs. |

| ↑11 | In fact, I don’t think it’s transformational, even in the broadest sense of that concept. The infringing software will do exactly what the copyrighted software does, in exactly the same context. |

| ↑12 | The other defense that could be raised in this sort of situation is copyright misuse, which derives from antitrust law: you can’t use your (legal) copyright monopoly to gain a monopoly on things outside of copyright law’s purview. I’ve never seen is applied where, as here, the copyrighted material is fairly well integrated into the device. This is a far cry from stamping a tiny little copyrighted emblem onto a watch to control otherwise legal importation of the watch. |