What an Antitrust Case Can Teach Us About Design

When I was in law school in the late 1990’s, it was an article of faith that the U.S. didn’t protect industrial design, but Europe did, and that’s why Europeans were so much better at it than Americans. Think, for example, of the emphasis that Italians and French reputedly place on design. More accurately, several European countries had specific protection regimes for industrial design, and the U.S. didn’t. In the U.S., you had to rely on a hodgepodge of different laws and just kind of hope1Kind of like software, except that Europe doesn’t have a separate protection regime for it.: copyright and trade dress mainly.

As it happens, at that time, Apple was calling that article of faith into question. It was relying heavily on industrial design to get itself back on its feet. It’s hard to believe now, but Apple was flat on its back in the 1990’s. Sure, it had Steve Jobs back, but it still needed something to make money, or else all its other plans wouldn’t even take off. In 1998, it introduced the iMac G3, and it looked beautiful: vibrant, cheerful and fun. Jason Fox hated it. Although it was competitive with the beige IBM-compatibles at the time, in terms of value and features, it wasn’t that great a value. The pre-OSX operating system was still clunky. Its main technological achievement was to kill off the floppy drive.

But it sold, and in my view, it sold based in large part on the industrial design. Thank Jonathan Ive for that (but also Jobs’ deep and abiding un-business-like affection for aesthetics).2For a perspective arguing that design might’ve had too much emphasis at Apple recently. Industrial design, the thing Americans were no good at. And the thing that U.S. law essentially didn’t protect.

This era of Apple design was marked by clean curves, prominent use of colorful and white translucent plastic, and emphasis on form following function (think especially of the handles on those iMac and especially the clamshell laptops). And there were a lot of imitators. I have at home an old PDA3Which was designed by Jeff Hawkins, himself a great product designer. and external floppy drive, complete with translucent Bondi blue (Apples most iconic color) cover. These imitators immediately made you think of Apple, but Apple couldn’t stop them (assuming it wanted to).

Was protection of design that important to nurture innovative industrial design? Did the Europeans’ protect of industrial design cause their mastery of design, or was it the other way around? I.e., did Europe just value design and naturally protect what it valued?

U.S. Design Law: Overlaps and Gaps

If you want to protect industrial design in the U.S., you have three options, which kind of overlap and aren’t great. The main problem is the “industrial” part of “industrial design.” Only utility patents can protect functionality4Trade secrets in theory can protect functionality, but obviously not when the functionality is part of the product design and thus there for all the world to see., and separating what’s functional from what’s ornamental can be mind-numbingly difficult. In addition, each type of suitable intellectual property has at least one major drawback:

- Copyright looks like the top choice, doesn’t it? You design something and, boom, you have copyright in the design. But in addition to the problems with functionality—look up “useful article” in the Copyright Act—but it has an originality requirement that is too much for many designs, and the scope of its protection is fairly limited (because the protection will be “thin”).

- Trade dress sounds like it’s just made for industrial design. It sounds almost a synonym, right? It isn’t. Trade dress is actually a species of trademark, which means that its effectiveness is a function of the consuming public’s recognition of its distinctiveness, i.e., the public sees the design as distinguishing a product from competing products5For a certain value of “competing.” Where the trade dress relates the product design (as opposed to the packaging), you’re required to prove “secondary meaning,” which I’ll explain in a moment, but suffice it to say that it’s hard to prove (or at least, it’s supposed to be).

- Design patents are actually designed to work for designs. You get them like other (“utility”) patents, which is part of the problem: they’re kind of expensive to get. They have to be “novel,” i.e, no one has every thought the design before. And they take time to get and have a limited lifespan. Also, the law governing their enforcement is an unholy mess because courts rarely encounter them. Ask Samsung how it feels about U.S. law governing design patents.

Mind the V-Gap

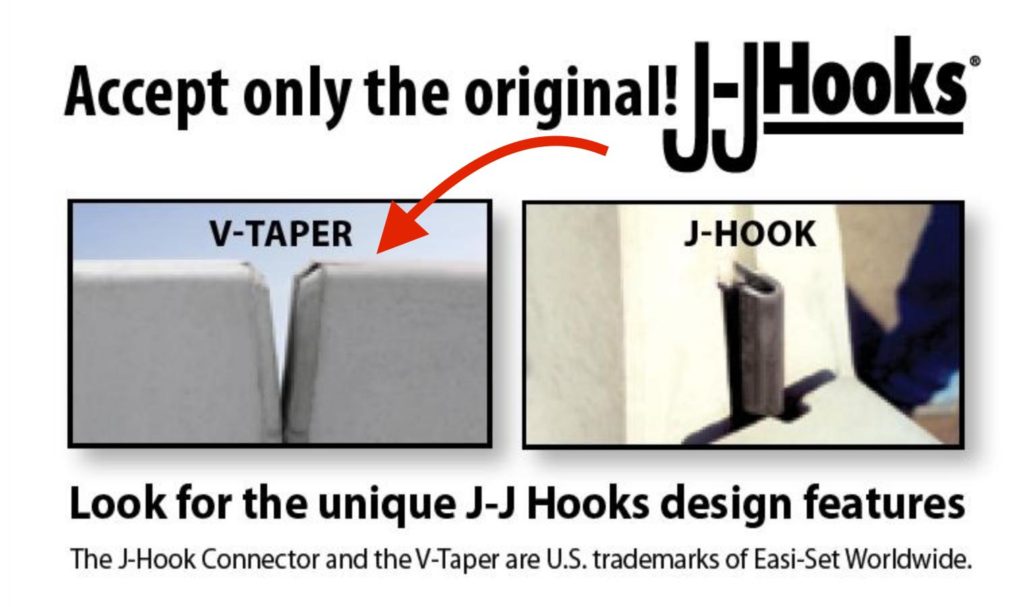

The industrial design I’m going to discuss is this:

Specifically, the “V-tapers.” What you’re looking at are traffic barriers, at the point where they join. The joining mechanism is down below, but at the top are these “V-tapers,” i.e., they taper slightly inward, so that when you put two together, it forms a thin V-shape.

Immediately, you can see that copyright isn’t a great choice. It’s not “original,” i.e., it doesn’t evince even the small modicum of human creativity necessary for copyright protection. It’s just a V-shape, and V-shapes belong to everyone. Remember that copyright protection isn’t very context dependent, so if you gave protection for this, you’d prevent the use of V-shapes in a number of unrelated contexts.

Design patent will have a similar problem. But instead of originality (you made it out of your own head), the problem is novelty (no one has ever made it). Surely someone, somewhere, has formed a V-shape by placing two tapered items together.

So that leaves trade dress. But trade dress is a real possibility. Trade dress doesn’t require originality or novelty. It just needs to be distinctive enough that consumers can tell it apart from competing products.

Oh, and it can’t be functional. Why is that so important? Trademarks (and trade dress) can last for a long, long time—so long as they’re used as trademarks by the trademark holder—but patents have a limited lifespan that’s short compared with other forms of intellectual property. If you have trademark protection to functional, you’d be giving patent-like protection but for a trademark-like period of time.6There are other considerations, too. Trademark protection is broader than patent protection, for instance.

Functionality/Dysfunctionality

Now, Easi-Set Worldwide, the folks who sell these J-J Hooks traffic barriers, with the “V-Taper,” went to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) and got a trademark registration (NOT patent) for the V-Taper.7Reminder: in the U.S., you don’t need a trademark registration to have trademark rights, which are developed only through use in commerce. Registration of a trademark confers many advantages, which is why so many people try to get one, but it’s not a requirement. To do so, it had to persuade the USPTO that the V-Taper had secondary meaning and that it was non-functional.

Now, something is functional if it provides a utilitarian advantage. Some utilitarian advantages are more obvious than others. If those V-Tapers somehow made it easier to install the traffic barriers, that would be a fairly obvious utilitarian advantage. If the V-Tapers save money by reducing the amount of material needed, that might also be a utilitarian advantage. The examiner had doubts about non-functionality, but Easi-Set won her over by showing a lot of competitors’ traffic barriers that worked perfectly well but didn’t have the V-Tapers. The idea is that, if the V-Tapers were so advantageous, someone else would be doing it. The registration issues. Good job Easi-Set trademark attorneys!

Standards: The Holy Grail of IP Law

Then it gets interesting. Easi-Set Worldwide apparently persuaded the Texas Department of Transportation (“TxDOT”) that all traffic barriers used in the Texas need to have these V-Tapers. This represents a kind of holy grail of intellectual property: you force people to infringe on your intellectual property, such that either (a) your competitors have to pay you for the right to comply with the law or standard, or (b) you have a monopoly over a crucial piece of infrastructure.

Most notoriously, you see this a lot with standards-setting organizations, like the IEEE, which try to industry players to play by the same set of rules so the engineering is simplified and consumers have more choice. For example, WiFi works according to standards laid down by the IEEE, so that a number of consumer devices may work seamlessly. If every WiFi system had its own system, you couldn’t be sure your device would work with it. Either your device would be a lot more complex and expensive, or you’d just have to take your chances. The risk with the standards is: what if complying with a standard infringed someone’s intellectual property? Or, worse, what if one of the industry participants in the standards setting had steered the standard so that it infringed its intellectual property?

But, wait a minute. Why would TxDOT require that all traffic barriers in Texas have V-Tapers if they weren’t functional?

It Might Be a Shame, but it’s Not a Sham.

Then, it apparently got weirder. When one of Easi-Set’s competitors complied with this requirement, Easi-Set demanded that it stop infringing its trade dress.

This competitor (which was already embroiled in a patent suit with Easi-Set) thought it smelled a rat. If traffic barriers in Texas must have the V-Tapers, but if using V-Tapers on traffic barriers infringes Easi-Set’s trade dress, doesn’t that give Easi-Set a monopoly in Texas over traffic barriers?

So the competitor sued Easi-Set for anti-trust violations and related unfair competition torts. It also sought to have the court cancel Easi-Set’s registrations for the V-Tapers.

The lawsuit is off to a bumpy start. The court threw out the anti-trust and anti-competition claims based on a First Amendment doctrine known as Noerr-Pennington. The Noerr-Pennington Doctrine is based on our right to petition government. In its original form, it allows competitors in the same industry to lobby a legislative body for laws that would benefit the industry as a whole, or even just the part of the industry to which the petitioners belong, without running afoul of anti-trust laws. Normally, if you and your competitors worked together like that to help each other, you’d risk an anti-trust claim because you should be competing to make better and/or cheaper products, not making life easier for everyone. But the First Amendment steps in and give you the right to trick gullible legislators to pass anti-competitive laws. In this case, Easi-Set is accused not of working in tandem with competitors but of “capturing” a state regulatorybody to the detriment of its competitors. Since Noerr-Pennington has been interpreted increasingly broadly over time, this is well within the scope of the doctrine.

But there’s an exception: if the petitioning was a “sham.” Lobbying activities are a “sham” if they are objectively baseless. The U.S. Supreme Court has held that lobbying efforts are not baseless if they worked, i.e., the regulatory body did what the petitioning party wanted it to do. For it to be a sham, the petitioning activity, not its outcome, must be the source of the anti-competitive effects. While this makes sense in the sense in the context of a lawsuit—if you win, then your lawsuit was by definition not baseless—it’s hard to imagine how lobbying could ever be a sham. Perhaps if you told the regulators falsehoods about your competitors?

The result was the sham exception didn’t apply because Easi-Set got what it wanted: a mandate that all traffic barriers in Texas use the V-Tapers, which just happen to be registered trade dress owned by Easi-Set.

The registration itself might be vulnerable to cancellation, on grounds that it is functional or on grounds that “the mark … is being used to violate the antitrust laws of the United States.”8The registration is more than five years old, but functionality and antitrust remain viable defenses against registration. I’ve never seen a challenge to a trademark registration on antitrust grounds, but this might be a first. I don’t think Noerr-Pennington would apply here because the statute is written in terms of the effect of the mark, not how the mark was obtained. The way I read it, the law just doesn’t want registrations out there causing this sort of antitrust trouble.

The case in still in early stages, so we’ll see how it goes.

That’s all for now. Thanks for reading!

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Kind of like software, except that Europe doesn’t have a separate protection regime for it. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | For a perspective arguing that design might’ve had too much emphasis at Apple recently. |

| ↑3 | Which was designed by Jeff Hawkins, himself a great product designer. |

| ↑4 | Trade secrets in theory can protect functionality, but obviously not when the functionality is part of the product design and thus there for all the world to see. |

| ↑5 | For a certain value of “competing.” |

| ↑6 | There are other considerations, too. Trademark protection is broader than patent protection, for instance. |

| ↑7 | Reminder: in the U.S., you don’t need a trademark registration to have trademark rights, which are developed only through use in commerce. Registration of a trademark confers many advantages, which is why so many people try to get one, but it’s not a requirement. |

| ↑8 | The registration is more than five years old, but functionality and antitrust remain viable defenses against registration. |